RDM’s Kevin Deenihan and Matt Jensen discuss fighting reptile theory in an article titled “Fighting Reptile Theory in Court: Making Plaintiffs’ Attorneys Feel Survival Danger” in the February 2016 issue of the Defense Research Institute‘s Trials and Tribulations. “Awareness of this vulnerability and familiarity with typical Reptile Theory tactics are keys to using this weakness against Plaintiffs’ counsel,” write Deenihan and Jensen. Read the entire article below.

Fighting Reptile Theory in Court: Making Plaintiffs’ Attorneys Feel Survival Danger

Reptile Theory’s insidious impact on the psychology of the individual has sparked a welcome defense interest in psychological concepts like cognitive bias and framing techniques. Not to be overlooked, however, is Reptile Theory’s alienation from traditional concepts of justice and fairness in the courtroom. At the very heart of Reptile Theory is throwing away the long-accepted ideal of a dispassionate jury arriving at a soundly reasoned truth. Reptile Theory even redefines the word “justice” up front, aware that the usual definition is at odds with Reptile Theory’s need for verdicts derived from frightened, primal self-interest. “The Reptile Speaks” starts chapter two with the statement “[j]ustice is of no interest to me except when it can help my genes survive.” See Reptile: The 2009 Manual of the Plaintiff’s Revolution, Ball and Keenan, 2009.

A. Redefining “Justice” is a Reptile Theory Weakness

However, “Justice” is not just another psychological concept to be used as a tool by Reptile Theory devotees. Justice as a concept underpins the way the American legal system works, the way the rules of evidence work, and the way legal duties and damages work. The rules of evidence in particular are a commitment to promote an ideal of dispassionate reasoning over what was long perceived as the danger of emotional, self-interested feeling. “A revolting crime, such as was committed here, requires unusual circumspection for its trial, so that dispassionate judgment may have sway over the inevitable tendency of the facts to introduce prejudice or passion into the judgment.” Fisher v. United States, 328 U.S. 463, 494 (1946) (Rutledge, dissenting). This means that Reptile Theory—which at its heart strives to influence jurors based on fear and self-preservation—is at odds with the rules of evidence and with long-inculcated judicial norms.

Awareness of this vulnerability and familiarity with typical Reptile Theory tactics are keys to using this weakness against Plaintiffs’ counsel.

Reptile Theory violates FRE 401, 402, and especially 403—and their state counterparts—in two essential ways. First, in order to motivate a fear response, it requires the use of inflammatory language, the invocation of bias and prejudice, and the development of self-selected “community” or “safety” standards contrary to the law at issue. Second, in order to personalize the perceived risk to the juror, it must introduce third-party materials from other industries, companies, or groups in order to create a sense of national trend or at least possible threat to the juror’s own community.

What’s your strategy?

RDM’s extensive trial experience can help you prepare for your next trial. Learn more about our approach and see what we can do for you.

Strongly consider a motion in limine to alert the Court that a predictable set of unrelated materials and issues will be introduced. Inform the Court in advance to expect questions related to “community,” and the “safest option.” Counsel should also be alert to references to corporations, industries, documents, trade associations, and research that have no foundational link to the Defendant or the action, and object appropriately.

1. Protect the Duty of Care

The Reptile strategy also directs plaintiff’s counsel to establish certain “rules” during the trial, because “errors and mistakes don’t motivate verdicts … safety rules do.” Reptile, p. 243. Plaintiffs create these “rule violations,” in large part, through the use of hypothetical, argumentative, and over-generalized safety questions during argument and witness examinations. However, alert counsel will object that these rules substitute invented safety rules for the duty of care that has long formed the basis of legal liability. Courts are protective of the duty of care, and suspicious of tacit attempts to overrule it. See Hottle v. Beech Aircraft Corp., 47 F.3d 106, 110 (4th Cir.1995). Courts have also rejected attempts to substitute industry standards for the duty of care. Rinkleff v. Knox, 375 N.W.2d 262, 266 (Iowa 1985). Judge Pamela Heffernan, in a medical malpractice case in state court in Utah, summarized the problem with Reptile Theory’s position as follows:

But what I have experienced is people talking about, instead of standard of care, they talk about safety rules. Safety is one thing, but safety rules as a substitute for the standard of care, that’s what I have seen argued. I don’t know if you intended to do that but that seems to be a very popular thing to say instead of talking about the doctor breached the standard of care (doesn’t have anything to do with auto rules, stop signs, etc.). It’s a standard of care that a professional is required to maintain in treating their patients and there has to be expert testimony on it and it has nothing to do with any kind of safety rules. No one wants to be unsafe when they go to a doctor or hospital. It applies sort of above and beyond the standard of care.

Hurley v. Parry, Motion in Limine Hearing Transcript, available at Waddoups v. Noorda, Case No. 1:11-cv-00133-CW-BCW, Document 295-3, Filed 6-4-14 (N.D. Utah).

2. The Golden Rule

Defense counsel should remember that specific rules were developed decades ago to combat the exact type of appeal Reptile Theory prescribes. In particular, courts consider “Golden Rule” arguments to be improper in the courtroom. See Blevins v. Cessna Aircraft Co., 728 F.2d 1576, 1580 (10th Cir. 1984) (“’Golden Rule’ evidence is ‘universally recognized as improper, because it encourages the jury to depart from neutrality and to decide the case on the basis of personal interest and bias rather than on the evidence.’”) (quoting Ivy v. Security Barge Lines, Inc., 585 F.2d 732, 741 (5th Cir.1978), rev’d on other grounds, 606 F.2d 524 (5th Cir.1979) (en banc). Golden Rule objections strike fundamentally at the premise of Reptile Theory—to personalize the case to the juror, and make the juror perceive a personal threat to his or her person. Reptile Theory is far from unaware of the risk of the Golden Rule—the book includes an entire appendix discussing Golden Rule standards and how to get around it.

Case law is clear that prohibited Golden Rule appeals are not limited to formulaic “stand in your shoes” appeals, but to any attempt to violate “the fundamental concept of an objective trial by an impartial jury.” People ex rel. Dept. of Public Works v. Graziado, 231 Cal.App.2d 525, 533-534 (1964). Be prepared to object to appeals to self-interest or other messages designed to break down the wall between jury and parties. Loth v. Truck-A-Way Corp., 60 Cal.App.4th 757, 765 (1998).

3. The Community

Another line of attack is to object to the importation of punitive concepts into an action. A long line of case law rejects the use of “send a message” and “punishment” concepts. “Send a message” arguments “divert[] the jury’s attention from its duty to decide the case based on the facts and the law instead of emotion” (Caudle v. District of Columbia, 707 F.3d 354, 361 (D.C. Cir. 2013)) and “impinge upon the jury’s duty to make an individualized determination (Sinisterra v. U.S., 600 F.3d 900, 910 (8th Cir. 2010)). Make sure to object when an argument by Plaintiff seeks to import punitive concepts. See e.g., Pleasance v. City of Chicago, 396 Ill.App.3d 824, 828 (2009) (“not the jury’s duty … to send a message to the community”); Scott v. Crestar Financial Corp., 928 A.2d 680, 685-87, 688 (D.C. 2007) (holding it improper to argue that jury is “the conscience of the community” which must “get through to” the defendant with its verdict); Koster Cruise Ltd. v. Grubbs, 762 So.2d 552, 554-555 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2000) (noting that an argument was a “clearly improper” “‘send a message’ argument[]” where it urged the jury to tell the defendant “by your verdict in this case to do something.”)

B. Conclusion

Reptile Theory treats its brash dismissal of longstanding notions of justice and impartiality as a strength. It is not. It leaves Reptile Theory arguments open to objections on numerous grounds—supplanting the duty of care, introducing golden rule arguments, introducing punitive awards, and generally using irrelevant and prejudicial materials. It rejects centuries-old standards of justice and fairness because they do not create enough verdicts for Plaintiffs. Informing the Court in advance of the predictable arguments of the Reptile, and preparing accordingly, will go a long ways towards effectively defending against—or precluding altogether—the Reptile at trial.

This article was originally published in DRI’s Trials and Tribulations newsletter, Volume 22 Issue 1, February 26th, 2016.

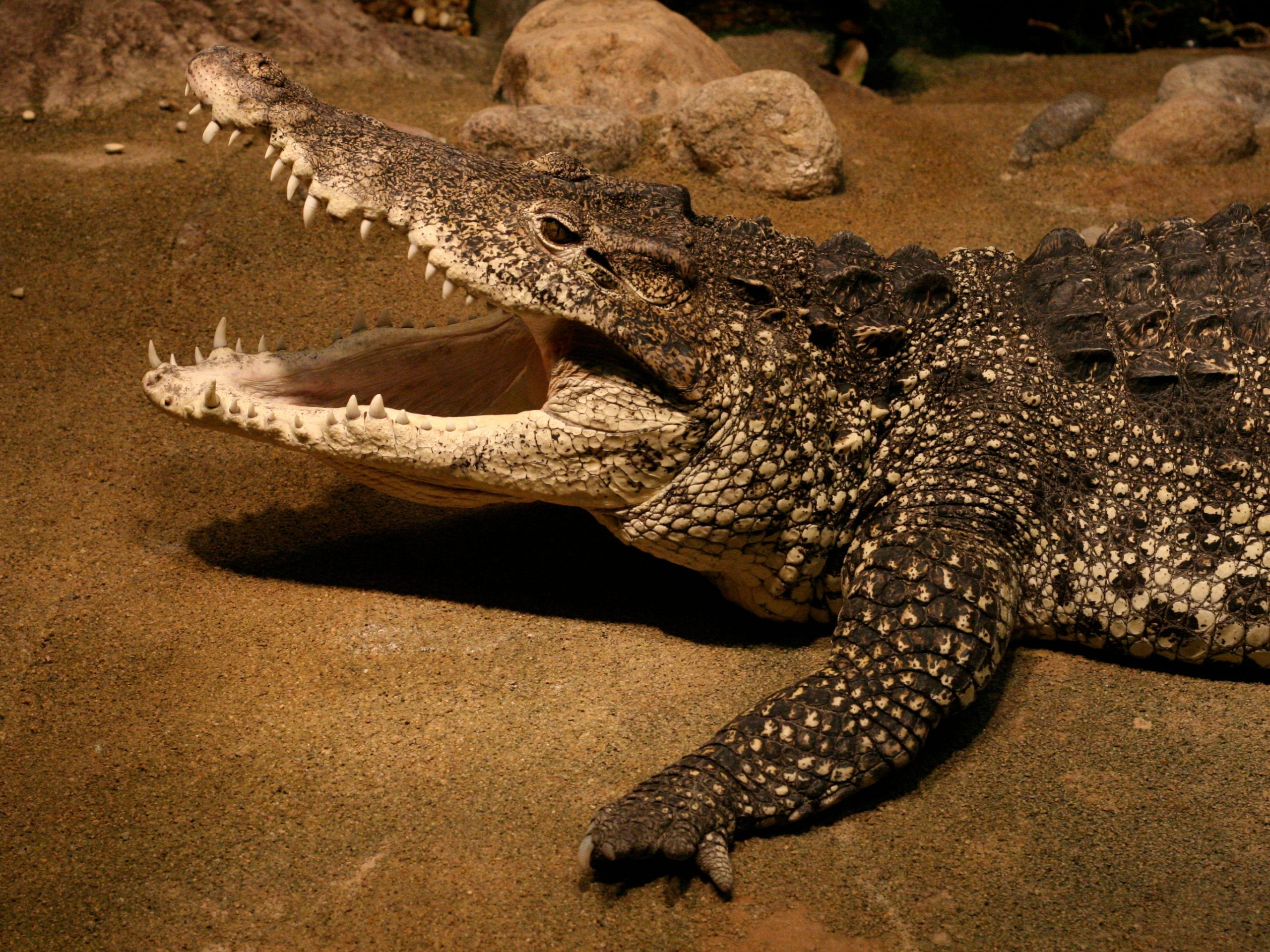

Photos courtesy of Flickr users Laura Wolf, Robert Moran, and Stefan Leijon.

Photos Flickr users Laura Wolf, Robert Moran, and Stefan Leijon.